The priest that went through hell

On St. Maximilian Kolbe‘s lessons of love, humanity and sacrifice

In late-July 1941, at Auschwitz, a prisoner escaped.

A seemingly impossible deed - prisoners were monitored almost every hour of the day, presented for a roll-call every morning (oftentimes naked), and the electrified fences were guarded with a wide margin that any approaching prisoner would be shot by. To escape the apogee of security is a miracle in itself.

That man was not Maximilian Kolbe. In fact, as far as I can tell, nobody knows who the escapee was - which, of course, is the point.

But Auschwitz, the emerging hell on earth, was not a place where the individual mattered. As Georgio Agamben wrote in Homo Sacer, the totalitarian concentration camp was a place where the things that made us individuals - and therefore human in the rich sense - were gradually stripped away. Prisoners were ritually shaved, stripped naked, branded, humiliated, dressed in uniform, and herded through the camp’s facilities to be either brutally and systematically murdered, or put to work in the worst possible conditions imaginable - because they ‘weren’t people’.

At least, not anymore, and certainly not in the mind of the mad ideologues who presided over them. At times cattle, other times pests, the Nazis (and the Soviets in their own way) viewed the prisoners as an inconvenience to be disposed of. That is what Homo Sacer means - ‘bare humanity’. Bare in the physical, moral, and social sense, the prisoners were stripped of, first, their national identities, then their communal identities, then their social identity, and finally their very personality. The prisoners of Auschwitz I (as the camp that formed part one of the Auschwitz-Birkenau complex came to be known) were utterly interchangeable with one another, until their time for extermination came.

So, when a brave soul made his escape, the guards responded in the way you might respond to a disobedient herd: ritual, exemplary punishment. Ten men were selected to be punished through starvation as an example to others who might dare to risk re-embracing their humanity. Of these ten men, one responded by screaming for his wife and children, who he feared would be worse without him there to protect them - itself a testament to the hope for the future, but the sheer scale of intentional ignorance the prisoners were kept in.

But one man stepped forward to take his place. That was Maximilian Kolbe.

Kolbe, a Polish Franciscan friar, had been serving in the monastery of Niepokalanów when the Germans invaded in 1939, before being arrested and subsequently released. A man of clear conviction, who viewed the world, as God calls us to, as a place of universal brotherhood, Kolbe had spent the early-1930s on mission in Asia, founding monasteries in Japan and India, before returning in 1933 to Poland.

Kolbe was not a man who often took the easy route - born Raymond Kolbe, he claimed that at the age of nine he was visited by a vision of Mother Mary, holding two crowns, one white (symbolising purity) and one red (symbolising martyrdom) and asking which he would choose. Young Kolbe said he would wear both. After the First World War, Kolbe spent his time in Poland publishing religious texts, running a theological press at Grodno, before establishing the Niepokalanów monastery as a seminary and publishing centre.

But when the war broke out, Kolbe was faced with his hardest choice yet. In the Nazi Reich, a twisted version of the principle of ethnic nationalism had emerged, encapsulated in the Deutsches Volksliste, an institution established to identify and indict into the Reich those of ‘ethnic German heritage’, which would give those persons access to all the rights and privileges that ‘true Germans’ could claim.

It is wrong to claim that saints are born; they are made in the moments of decision that offer the worldly pleasures of the Devil, or the promise of eternal salvation with God. For Kolbe, the decision was not easy, as it never is, but it was obvious. As a Christian man who had viewed the world as a universal brotherhood, while rejecting the leftist (and especially communist) movements of the 1920s and 1930s, for Kolbe nationalism was a link in a chain, not the terminus; it connects us to the community of the world, not sever us from it. The Deutsches Volksliste cut that link, and so he would not sign it, knowing it would be the harder decision, but ultimately the right one.

The first and obvious victims of the Nazi evil was the Jewish people, which is why the Catholic monastery was given a slim margin of freedom in publishing religious texts. But in early 1941, the monastery was finally shut down, and Kolbe arrested for the second and last time. He was interned in Auschwitz on the 28th May, becoming prisoner 16670.

True to his nature, Kolbe continued to serve the Lord in the midst of the worst conditions that had ever been imposed on other human beings, administering to prisoners, offering last rites, and tending to the wounded. No good works go unpunished though, and he was subject to continual beatings, being smuggled into a prison hospital on one occasion.

That’s why, in July 1941, Kolbe’s decision to take the condemned man’s place was not the easy decision - but it was the obvious one.

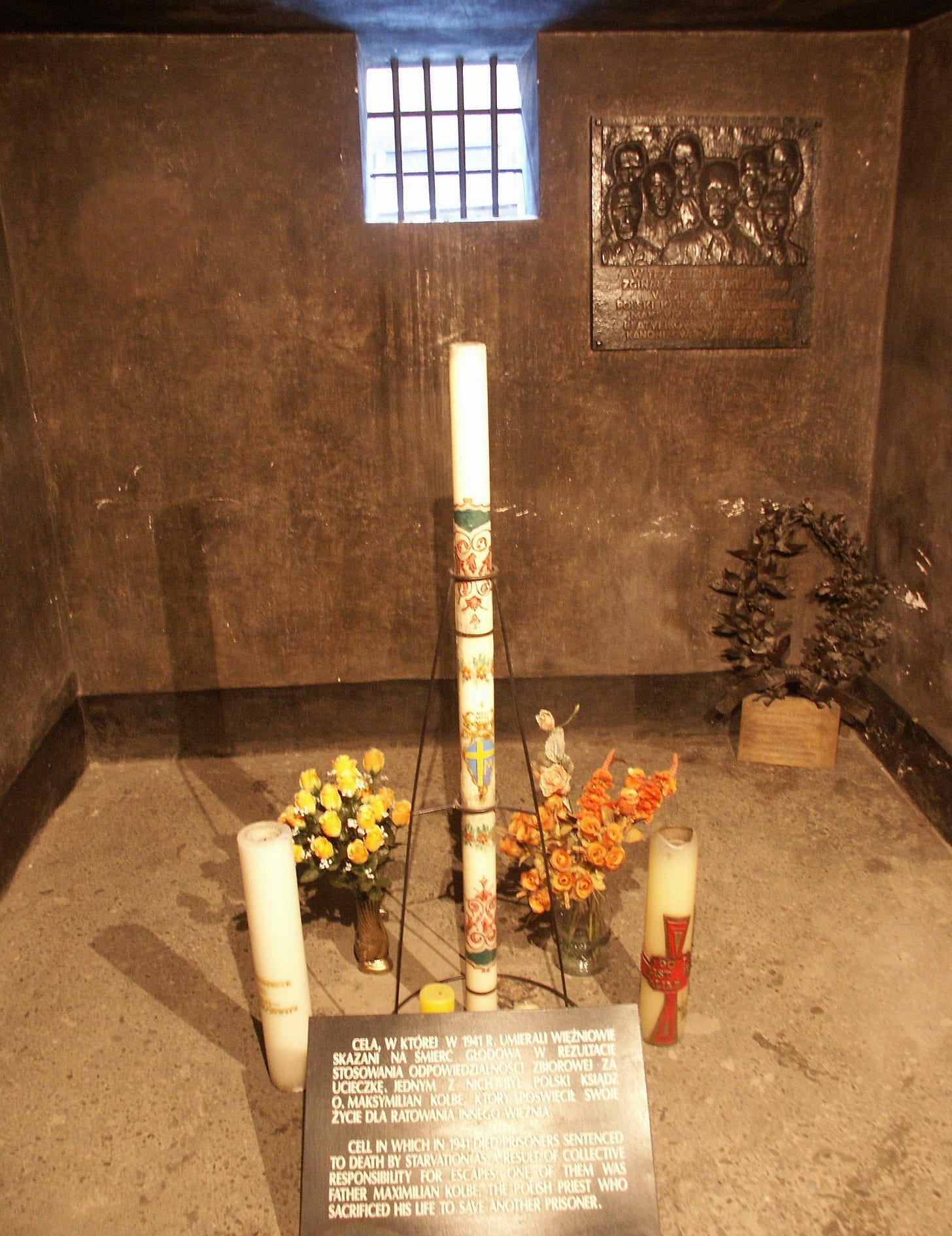

Kolbe and his fellow nine inmates were shut in cell block 11 of the Auschwitz prison, where they were starved of food and water for two weeks. Reports go that every time the guards would open the door to fetch the bodies of their victims, or administer their own cruelty, Kolbe could be found either kneeling or standing in the centre of the cell, praying for the souls of all those around him - including his guards. After the two weeks had passed, only four men were left alive, of which Kolbe was one.

Again, for his good work, he was put to death, with a lethal injection into the heart on the 14th August 1941. As with everything in his life, Kolbe faced death calmly and with stoicism, knowing that it wasn’t the easy option. But it was the obvious decision.

Maximilian Kolbe became Saint Maximilian on the 10th October 1982 by Pope John Paul II, a fellow Polish priest (Karol Józef Wojtyła). Saint Maximilian was the second saint to be canonised by Pope John Paul II, and the first of his own lifetime.

I recently visited Auschwitz-Birkenau. I had intended to go for several years, but the pandemic and a series of personal occasions prevented the visit. It is harrowing, bleak, silent, still, and utterly terrifying: the industrial scale of slaughter that had been unimaginable only a few generations before was routinised and rationalised while the individuals interned there were stripped of anything that made them human. Every scene will be seared into my mind.

I had first read the story of Maximilian Kolbe in Sohrab Ahmari’s excellent The Unbroken Thread, and had been desperate to visit the shrine of the saint ever since; and the prison cell in which Kolbe defied all attempts to make him lose his humanity was like a single flame guttering in an oppressive dark. You can’t linger, or take pictures, but the shrine there is a reminder of the importance of humanity in a world gone mad.

In the midst of the hell that Auschwitz-Birkenau, and the many other camps that the Nazis built across Europe, summoned forth onto earth, there were still men prepared to hold onto and fight for what was right. Kolbe’s story is one that shows us the importance of holding onto love for one another, and the power of God in the face of pure evil. The right choice is always obvious to us - the power to make it is ours.