Eight years ago, a Romanian man returned from Turkey to discover that he was dead. Not literally, nor even metaphorically, but the worst kind - bureaucratically.

The story is not so sinister as it sounds: apparently, in 2003, the man’s wife secured a death certificate for him after losing contact with him and assuming he had died in an earthquake in Turkey. Despite turning up in court himself to contest the declaration of his death, the man’s claim was denied and refuted - he had, after all, no legal documentation to prove his own existence.

Such absurdity belongs in the post-Soviet fringe, where bureaucracy reigns supreme and the system decides who lives and dies. At least, so goes the propaganda; by some quirk of fate, a similar story emerged in the heartland of Western capitalism, with a Seattle man being declared legally dead.

The story, in this case, is not so sinister either, but it is certainly more political. DOGE, as part of its crusade to cut costs, has zeroed-in on the absurdity that is the American Social Security system, with Elon Musk digitally brandishing a spreadsheet of the numbers of Americans in certain age brackets receiving Social Security payments - with scores of people over the age of 110 benefiting so.

In this instance, it was not an angry spouse but a zealous reformer. As part of the grand revision of Social Security, DOGE’s bureaucrats decided that Mr. Ned Johnson, aged 82, was dead; subsequently, his widow was informed, as was his bank and - despite his protestations to the contrary - the bank simply did not believe the man they were speaking to was alive. Moreover, Ned was told he hadn’t simply passed away recently, but he actually died in November, so his Social Security payments for December and January were withdrawn from his bank account as they were retroactively reclaimed.

Such absurdity belongs in the post-Soviet fringe, where bureaucracy reigns supreme and the system decides who lives and dies. At least, so goes the propaganda.

We all have stories of dealing with bureaucracy, of trying to find the right documentation and then getting frustrated when it’s either not accepted or insufficient. I doubt, though, many of us have been told we’re dead and then not been believed no matter how much we’re alive.

If there’s a lesson to take here, it’s this: bureaucracy does not care about the individual. To bureaucracy, the “individual” is a data point that completes a chain of information fed through a system, and the logic of the system requires that it must roll on, smoothing out wrinkles and processing incompatible data as errors. Because it cannot be the system that is at fault, can it?

This is largely because bureaucracy does not have a face - or more specifically, eyes. As a result, it cannot see exactly that which is in front of it; the evidence contrary to its own beliefs. Even worse, bureaucracy breeds bureaucrats, and bureaucrats are bound by the processes to which they are responsible, since it is the process alone that put them there. When bureaucrats decide, it tends to be permanent, and the humanity of the people involved tends to be smoothed out in favour of the data that informs the process. I hope Mr Johnson is able to get his welfare - or at the very least, console his grieving widow.

Over 60 years ago, one political theorist did her best to warn against the bureaucratisation of life by examining its most grotesque and absurd version. Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil was written after Arendt, an early escapee and survivor of the holocaust, came face to face with Adolf Eichmann, the man responsible for designing the processes that facilitated the ‘Final Solution’.

In Arendt’s shoes, you would expect that the man you’re about to see is the very personification of evil, in whatever way you might picture that, as the man responsible for the murder of hundreds of thousands of people, many whom you probably knew quite well. But, as Thomas White wrote, ‘Arendt found Eichmann an ordinary, rather bland, bureaucrat, who in her words, was ‘neither perverted nor sadistic’, but ‘terrifyingly normal’.’

Indeed, it is Eichmann by whom the phrase ‘just following orders’ was popularised. When confronted, not just with his crimes, but the victims of his crimes, Arendt was struck by Eichmann’s retreat into the process, not trying to defend or justify it but simply state its existence and observe his role in it. Arendt herself said:

I was struck by the manifest shallowness in the doer [ie Eichmann] which made it impossible to trace the uncontestable evil of his deeds to any deeper level of roots or motives. The deeds were monstrous, but the doer – at least the very effective one now on trial – was quite ordinary, commonplace, and neither demonic nor monstrous.

None of this is to compare like for like: the accidental erasure of a man’s Social Security entry, and the reasonable assumption that a man who nobody has heard from for years has died, cannot be compared to the intentional, mechanistic and monstrous murder of millions of people for no other reason than their race. But Arendt’s point was that the scale of evil no longer matters in conditions of modernity; instead, it is modernity itself, and the enormity of social life composed of millions of people, that makes it difficult to see the humanity in others. We retreat from dealing with individuals as individuals, and find security in seeing one another as data points, or numbers, or statistics - seeing, but not seeing.

Arendt’s argument is often obscured by the subject she studied: totalitarianism, and its impacts on human life, were novel, but it was the effect and not the cause of a wider condition. That condition is modernity, and the symbol of modernity is the mob.

Arendt observed that human societies - polities - emerged in conditions that were significantly smaller than ours, with Aristotle himself suggesting that 100,000 should be the upper limit of human communities. In a world where cities number several million, how can the human mind deal with this? One of the best examples I’ve seen of this conceptualisation problem runs as follows:

Let’s say you earned £10,000 every day from the birth of Jesus Christ until now. Your net worth would still be one-fifth of Elon Musk’s.

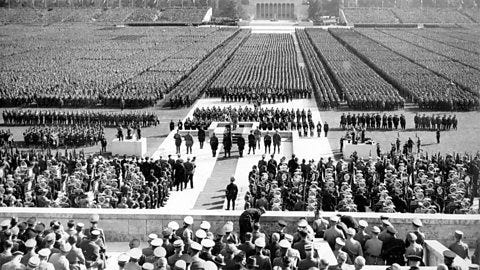

I’m not trying to moralise wealth, but help to show the problem of conceptualising numbers in the human mind. Have you ever been in a room of 100 people? The largest single crowd I’ve spoken to is 350, at a first year lecture; to try and conceptualise a crowd of 1,000,000 boggles my mind. That is part of the reason the rallies the Nazis held were so (for lack of a better word) ‘impressive’: not just the scale, but the organisation.

Now try and imagine being one person in that crowd. The violence of the regime and the everyday cruelty it inspired was, suggested Arendt, a consequence of the inability to conceptualise oneself as an individual in such a crowd. Put simply, it was not just Eichmann, ‘managing’ such mobs, whose humanity disappeared, but the members of the mobs themselves.

I’ll reiterate it, in case someone suggests otherwise: I am not comparing like for like. But if we’re struggling to understand how human beings can forget to see one another as human beings in the modern world, consider Arendt’s answer: it’s because we both cannot, and do not need to. We do not have the mental capacity to understand communities at such scale, so we have built processes to manage them; processes that are reasonable and necessary but require supervision and a human to manage.

As we approach an era of mass automation, please bear the 1970s slogan of IBM in mind:

A computer can never be held accountable, therefore a computer must never make a management decision.