The infrastructural problem

Services and identity are a numbers game that we’re losing.

In 1856, Joseph Bazalgette, the chief engineer tasked with designing London’s new sewer system, made a decision that confused his contemporaries: he doubled the diameter of the pipes.

The already-generous dimensions of the pipes should have been able to more than accommodate the existing population of London, then two million, as well as preparing for future exponential growth to four million. But Bazalgette’s decision, expensive though it was, was ‘unbelievably prescient, as had he not done so London’s sewers would have overflowed in the 1960s’, when the population of London reached eight million.

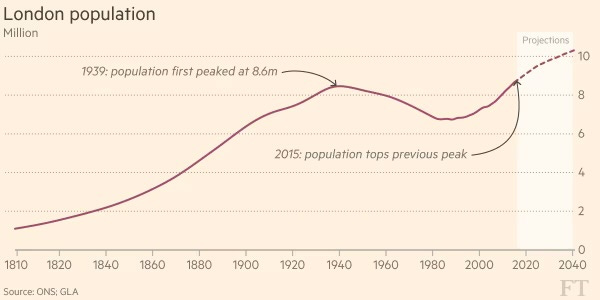

Except, this is not the first time London’s population was so large. As far as estimates and censuses go, London’s population last reached eight-and-a-half million in 1939, on the eve of war. So, why are we at such capacity now?

London’s, and the country’s, waste problem has never really disappeared - nobody needs reminding of the scenes just last year of the stained and bruised coasts of England that led to water sanitation warnings up and down the country. Fortunately, after ten years of construction, London’s ‘super sewer’ is finally operational. Expected to prevent 95% of spills into the Thames, the Tideway Tunnel should help the capital’s struggling sewers as the population swells to nine million.

Except, this is not the first time London’s population was so large. As far as estimates and censuses go, London’s population last reached eight-and-a-half million in 1939, on the eve of war. Thereafter - for reasons obvious and nuanced - the population of London actually declined, as the Financial Times has neatly plotted.

If London’s population had been on an upward trajectory for a century after 1856, alongside the increased use of indoor plumbing, the story might be easier to tell (the Housing and Town Planning Act 1919 required all new homes to have toilets, though the gradual expansion of grants to improve the existing stock of houses was only developed from the late-1940s through to the 1980s). Nevertheless, these two factors were in balance, meaning that the declining population of London offset the increasing strain on the city’s plumbing system.

So, why are we at such capacity now? The reason is we simply do not have the data to know. As the Adam Smith Institute’s Sam Bidwell has deftly pointed out, our capacity to count the occupants of this country has collapsed, potentially worse than it was in the Victorian era. The closest estimate we have to actual numbers comes, rather than censuses, from service use: for example, GP sign-ups, vaccination registrations and, of course, water use.

But, as Bidwell points out:

If the British state is bad at population estimates, the private sector is no better. A recent report conducted by Edge Analytics on behalf of Thames Water suggested that as many as one in 12 people could be living in London illegally. However, the methodology was far from robust. Rather than measuring actual water usage, it used out-of-date migration estimates from 2017 and assumed the irregular migrant population peaked the previous year.

The report Bidwell is referencing suggests that there could well be 550,000 more people in London than expected - because they are here illegally - but that only covers central London, and not Greater London. Alongside this, as the Prosperity Institute’s Guy Dampier writes, estimates (which are themselves badly outdated) suggest as many as 1.2 million illegal immigrants are living in Britain.

The sad reality is that we’re playing catch-up, but we’re doing so with out of date data, and we’re building for current demands. We’re not learning from Bazalgette’s example, and building for the future.

This is why it is hard to get excited about the infrastructural projects announced by the current government, such as plans to fill in Britain’s potholes and build seven new reservoirs. Don’t confuse the point: it is beyond overdue. But when the government’s plans include only £4.8bn to fix potholes, when it is estimated that it would cost £17bn to fix all of them, and the last reservoir was built in 1992, in Derbyshire, we simply are not doing enough, and what we are doing far too late.

It’s the same with the railways. The continual reduction in scope of HS2 is a case study all in itself, but the simple fact is we don’t have the capacity necessary to support the rapidly escalating demands. In 2003, annual demand was estimated at 975.5m passengers - this has nearly doubled to 1.759bn in 2019 at its peak, though this has since dipped to 1.385bn - meanwhile the number of route kilometres has stayed completely static for the last few years. We have more people using the railways, but haven’t expanded our supply.

The sad reality is that we’re playing catch-up, but we’re doing so with out of date data, and we’re building for current demands. We’re not learning from Bazalgette’s example, and building for the future.

Inevitably this leads to conversations on housing. We have not built anywhere near enough houses for the number of people living here. This is a topic nobody needs to hear more about, but the problem compounds itself because, when we do build houses, we don’t build the infrastructure necessary to accommodate the additional demand on local services.

One particular example near where I live, in Rugby, has been to plan to construct over 2,500 houses in the surrounding areas. One village in particular, Brinklow, looks set to be quite literally doubled in size, with plans to build 450 houses in the village. Given that the national average of occupants per household is 2.4, and the 2021 census showed Brinklow has 1,120 residents (as reliable as those numbers are), we can reasonably assume that there are roughly 466 houses in Brinklow. It is not hyperbole to say this village will double in size, at least geographically and almost certainly in terms of occupants.

As far as I can tell, there have been no concurrent plans to expand the infrastructural support for Brinklow. The village has one General Practitioner’s surgery, only one village shop, and - from experience - very narrow roads. The sheer scale of increase will be hard to accommodate as it is.

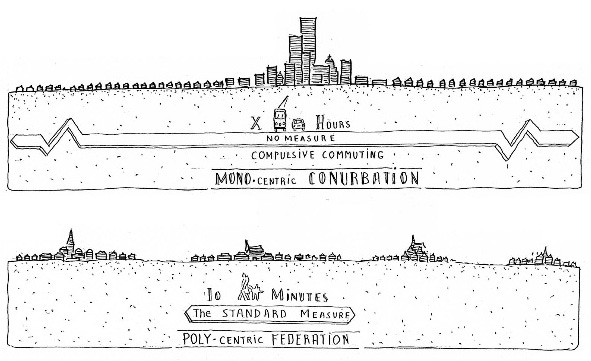

One of the great architectural theorists of our time, Leon Krier, analysed the organic evolution of neighbourhoods from villages to towns to cities as dependent on cultural centres. Put simply,

According to Krier, in order to retain this human scale, when a city needs to expand, it should duplicate its centre and so retain proximity between residents and services, rather than sprawling and centralising.

The great mistake of urban planning, Krier argues, is that the existing centre is simply left as it is, and the periphery only grows. If you expand towns this way, you’re not even replicating the natural evolution of towns historically; really, you should build additional high streets, even out of the centre.

But one thing that can never be accommodated for, infrastructural or not, is culture. Culture, for better or for worse, is a numbers game, and culture as an adaptive phenomenon always responds to numbers. Nobody would argue, for example, the culture in a room of 45 people would remain exactly the same when 45 people are added to that room at the same time. It may retain, in a Ship of Theseus style phenomenon, elements of continuity if those 45 people are added one after another, but simply not all at once. And certainly not when those people arrive with their own cultures.

Culture, here, does not mean anything so specific as a national culture; indeed, England was historically remarkable for its settled landscape and towns that produced distinct cultures and dialects as much as 30 miles apart (usually because that was a day’s ride away). But when the cultural centres that ensured a continuity of a specific identity - churches, pubs, cricket fields, secondary schools, etc. - are not replicated in the multiplication of centres that Krier argues for, the chances for cultural continuity are slimmed even further.