Social media is real life

Adolescence, Reform UK, and the blurred line of the internet

Is the internet real life? If you’ve browsed the internet at all in the last few days, you may be surprised to be confronted with posts on the internet telling you it’s not in some cases, and very much is in others. But between the growing fears of radicalisation, ignorance over the long-term reality of posting online, and the eruption of the feud within Reform UK, it is getting harder and harder to believe that the internet is a discrete space that exists alongside the private and the public.

Bursting onto the screens of Netflix - and buoyed by a direct mention in the Commons by Labour MP Annaliese Midgely - is Jack Thorne’s Adolescence, a show about the dangerous rise of toxic masculinity, embodied by the likes of Andrew Tate. I haven’t watched the show, so I’m not commenting on it, but Thorne is a fully signed-up member of the smartphone-free childhood movement - unsurprisingly.

Bursting out of the Commons at an almost contemporary moment was the (apparently long-hidden) feud between Nigel Farage MP and Rupert Lowe MP, of Clacton and Great Yarmouth respectively. Again, I don’t want to comment on the nitty-gritty of this feud, but what caught my eye was the discourse around the feud used by some to make a judgement over which side, if only strategically, Reform supporters should come down on.

The most common talking point I saw was that, quite simply, Farage is a political rock-star, and almost nobody knows who Rupert Lowe is. This was proved, if proof you needed, by a JL Partners poll that showed 86% of the public did not recognise Lowe when shown a photograph of him - and neither did seven in 10 Reform voters. This was presented by many sympathetic to Farage is a fait accompli, as if popularity now determines popularity in the future. But unfortunately, it does not really go that way.

If we remember that this is Lowe’s first (and, likely, final) stint in Westminster, alongside the long-standing average that 75% of the British public cannot name their MP, this is not enormously surprising. Not only that, but Lowe is (or was) a member of one of the smallest parties in Westminster, for all of the buzz around Reform. When one takes these points alongside the fact that, shortly after the 2015 election, members of the shadow cabinet enjoyed similar levels of recognition amongst the British public, Lowe’s low-level recognition seem less anomalous.

On the contrary, Farage has been one of the most recognisable politicians for well over a decade now. But he has only been an MP for less than a year. Recognition does not always mean popularity, and it almost never guarantees anything.

But back to the wider point: is social media reality? This flash-in-the-pan feud is hardly new in British politics - and, if anything, proves Reform are a bona fide Westminster party, in the same way a barman isn’t a barman until he breaks a glass. Well, on the one hand, we have the fair and reasonable point that Lowe’s success on X especially does not a political career make.

This flash-in-the-pan feud is hardly new in British politics - and, if anything, proves Reform are a bona fide Westminster party, in the same way a barman isn’t a barman until he breaks a glass.

On the other hand, there are some pretty seismic changes that have come about due to their relationship with social media. First of all, the grooming gangs scandal. Bubbling away for over a decade, it wasn’t really until Max Tempers, then Sam Bidwell, then Elon Musk(!) shared quotes from the sentencing remarks, as well as the context for an international audience, that it transformed public discourse, basically overnight. Labour are still being hammered on calls for a public enquiry, and their lack of action will definitely play a role in the next election, if either the Conservatives or Reform are savvy enough to make it relevant again.

We may not even have to wait that long - as Connor Tomlinson pointed out, the issue has inextricably linked immigration with violence against women and girls. In British politics at the moment, once an issue gets linked to immigration, it is very unlikely to go away.

Second, the 2016 Brexit vote (and the following nine years) have seen social media play a role in politics on a scale never appreciated before. Much ink was spilled obsessing over the idea that social media had completely swayed the 2016 vote, with German academic Max Hanska pointing out that Eurosceptic Twitter users ‘outnumbered and out-tweeted pro-Europeans’, while in 2019 the Guardian declared that Reform’s predecessor, the Brexit Party ‘won [the] Euro elections on social media’. A great comparative study from 2018 (Gorodnichenko, Pham and Talavera) looking at Brexit and the US presidential election made the point that, for the first time, ‘bots’ were effectively utilised to influence elections.

Third, the emergence of DOGE in America can be attributed almost to developments on social media. It’s hard put it all in order, but the salient facts are that Elon Musk’s purchase of Twitter/X was partly driven by a recognition of the collapse in free speech on the internet, followed by Musk taking a greater interest in American politics, before eventually becoming intertwined with the MAGA movement and, of course, financing Donald Trump’s 2024 run. But the specific name DOGE is inspired, of course, by a pun - Musk found the original meme of Kabosu, the shiba inu who became known as ‘doge’, to be absolutely hilarious, and tweeted ‘Doge’ in 2020, followed by tweets by Musk in 2021 saying that ‘Dogecoin is the people’s crypto’ because, by this point, Musk had emerged himself as the intersection between populism, memes and cryptocoins, of which Dogecoin was merely one. Eventually, this morphed into the meme that the ‘Department of Government Efficiency’ (DOGE) should be a thing. Almost none of this took place offline.

Fourth, and much older (by internet standards), the Arab Spring. Its reverberations still being felt today, the Spring was dubbed the social media revolution, ‘due to the widespread use of social network platforms. Their presence could be perceived as a cornerstone mostly in Tunisia, where the revolution started, and Egypt’. Of course, the internet did not cause the revolution(s), but it did amplify, connect, and provide new platforms for the many protest movements across the MENA region. If you’re sceptical, the Syrian Civil War began due to the Arab Spring - and it has ended with a probably even more bloody regime in place than the Ba’athist state in 2011.

So, with that in mind, I do not think we can discount the role that social media plays in politics, or indeed in real life. But to bring it back to Britain, I think we need to completely reject the idea that the digital space can continue to be thought of as a discrete realm from reality. And for Reform, there are some specific considerations to bear in mind that mean that, even if Lowe is not the man for Reform, dismissing social media as ‘not real life’, should be done very carefully.

To return to Jack Thorpe’s complaints, there certainly is good reason to be cautious over the mass use of smartphones amongst younger people: in 2024, 98% of children between 16 and 17 owned a smartphone, meaning the role that the internet plays in peoples’ lives is only bound to increase. Likewise, we should play particular attention to TikTok, one quarter of the users of which are under the age of 20, and a platform on which Reform’s account is huge. It has four million likes and over 373,000 followers, compared to the Conservatives’ 92,000 followers and Labour’s 230,000.

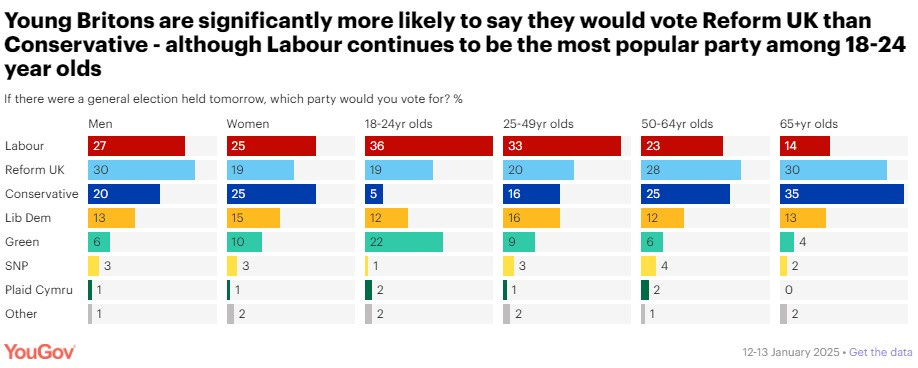

Meanwhile, if we assume (as I think we should) that the internet already plays a major role in the lives of young people, then we can explain the combination of factors that led to Reform polling higher than the Conservatives for every age group under the age of 65.

If the youth are increasingly online, and increasingly right-wing, and increasingly radical, then the fate of Reform is intimately connected to the internet. Dismissing the internet as “not real life” is dangerously short-sighted.